[Warning: The following contains spoilers for Season 1 of Last Samurai Standing.]

Surrounded by uniformed snipers, a crowd of contestants gather at a secret location. Soon they will be forced to fight to the death, spurred on by the slim chance of winning a colossal cash prize. Elsewhere, hidden carefully from view, a group of wealthy spectators crack jokes and place bets on which players will survive.

The similarities between Squid Game and Netflix’s new martial arts series Last Samurai Standing are not exactly subtle. In fact, it’s tempting to speculate that this show was greenlit with the platform’s recommendation algorithm in mind, selected because it resembles a well-known hit. Netflix seems keen to recapture Squid Game‘s magic, striking gold with a Japanese novel adaptation exploring a similar Battle Royale scenario. But can Last Samurai Standing fill the Squid Game void? And is it even fair to judge it on those terms?

Set in 19th century Japan, shortly after the Meiji Restoration, the story opens in the midst of a devastating cholera outbreak, during a period of cultural upheaval. Replacing the feudal structure of the Tokugawa shogunate, the new government has abolished the samurai system, upending the lives of men like our protagonist, Shujiro Saga (Junichi Okada). Forbidden to use his primary skillset as a swordsman, he and his family now live in poverty — until a peculiar advertisement brings him out of retirement. An anonymous benefactor has invited warriors from across Japan to meet in Kyoto, recruiting for an illegal martial arts contest with a staggering prize of 100 billion yen.

Naturally, this pitch is too good to be true. When the contestants arrive, they sign up without fully understanding the deadly nature of the event, a game nicknamed “kodoku,” where 292 players will race on foot from Kyoto to Tokyo. The route is lined with checkpoints, and contestants can only pass through if they’ve killed a certain number of their opponents. If they try to quit, or reveal the nature of the game to the general public, then they’ll be executed by the organizer’s private army.

Complicating matters further, Shujiro is struggling with PTSD and has lost his appetite for violence. He also decides to pair up with an inexperienced teenage girl named Futaba (Yumia Fujisaki), who’d clearly die without his protection. Once again, it’s easy to spot the overlap with allegorical survival thrillers like Squid Game and The Hunger Games, where desperate characters are forced to risk their lives for other people’s entertainment. Both Shujiro and Futaba are here for the same reason: Their families are sick with cholera, and they need the prize money to pay for medicine.

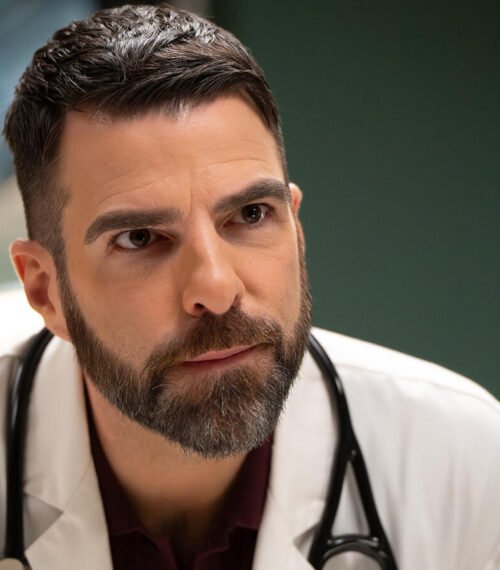

Over six episodes, Shujiro and Futaba’s adventures introduce a field of competitors who range from traditional-minded samurai to remorseless serial killers. As they make their way toward Tokyo, we learn more about the game’s shadowy organizer, Toshiyoshi Kawaji (Gaku Hamada), the real-life founder of the Meiji government’s police force. Motivated by a personal vendetta, he’s using the contest to kill as many samurai as possible.

Even if you know nothing about Meiji-era Japan, Last Samurai Standing sets out its political vision in easily comprehensible terms, beginning with the visual contrast between the tournament’s ragtag participants and Japan’s new ruling class. Embodying the old way of life, Shujiro and his fellow contestants are mostly dressed in traditional Japanese clothing, adhering to a romanticized vision of martial arts heroism. Meanwhile, the game’s overseers wear European suits and militaristic uniforms, echoing the Westernization of the Meiji government.

From these two factions, Shujiro and Kawaji emerge as aesthetic and spiritual opposites: Shujiro as a troubled but honorable warrior, still wearing a rough version of old-fashioned samurai dress; and the smug, mustachioed Kawaji, clad in a spiffy police uniform that makes him look more like a bellhop than a supervillain. Funded by a group of businessmen, he’s concocted an elaborate infrastructure to keep the tournament running in plain sight, staying one step ahead of government investigators. By the end of the season, it’s clear that Kawaji has greater ambitions than simply orchestrating some bloody entertainment for his friends.

With the Meiji setting providing a grounded historical backdrop, Shujiro and his fellow competitors exist in a more stylized martial arts world. Here, famous warriors have celebrity nicknames (“Kokushu the Manslayer”; “Bukotsu the Savage Slasher”), and everyone gets a genre-appropriate backstory involving tragedy, revenge, or betrayal. Prior to his samurai career, Shujiro himself grew up in a hidden mountain enclave, where he and his adoptive siblings trained for years to master the sword. Long estranged, these siblings are reunited by the kodoku tournament — where they’re all being hunted by an ominous, quasi-superhuman old man, who has vowed to kill them all for abandoning their training.

With fight scenes choreographed by lead actor Junichi Okada, Last Samurai Standing is obviously more action-focused than Squid Game — but more importantly, its broader storytelling choices are shaped by martial arts tropes. We learn about the characters through the way they fight and strategize, and we’re partly here for the simple pleasure of watching trained experts try to murder each other in cool ways. This is the kind of show where a villain kicks off a duel by announcing, “When two old friends reunite, they either share drinks together… or they kill each other.” Objectively nonsensical? Sure! But appropriate in context.

ALSO READ: The complete guide to fall TV

I won’t pretend this is one of Netflix’s absolute must-watch releases, but if anything, the Squid Game comparisons will do more harm than good. In Season 1 at least, Squid Game‘s ruthless plot twists and bleak social commentary felt like nothing else on TV. And Last Samurai Standing just isn’t that clever. Its relationships and moral dilemmas don’t pack the same emotional punch, and despite the obvious thematic callbacks, it doesn’t actually function like a Squid Game-style psychological thriller.

When I notice similarities between Shujiro’s moral code and Seong Gi-hun’s rigid pacifism in Squid Game, or between the Greek choruses of voyeuristic businessmen in both shows, these details mostly serve as a reminder of how Last Samurai Standing fails to measure up. But if we focus on qualities that are unique to this show, it’s much easier to get invested. First and foremost, this is an action series helmed by an experienced action star, and the specificity of the setting is a key appeal in itself. Then in the season finale, the tournament storyline links up to a real historical assassination, suggesting that Season 2 (if it happens) may shift further away from the show’s Squid Game-like starting point.

Netflix wants to keep audiences on its platform, so there’s a logic to the idea of championing new projects that echo familiar titles. But direct copycats rarely work. Every streaming service spent the 2010s trying to find its own Game of Thrones, resulting in an awful lot of overpriced sci-fi/fantasy dramas that failed to reach the same mainstream audience. Likewise, Last Samurai Standing isn’t, and never could be, the next Squid Game. Fans of Squid Game are more likely to find the similarities underwhelming, when Last Samurai’s true strengths lie elsewhere, succeeding more on the show’s own terms as a historical action series.

Season 1 of Last Samurai Standing is now streaming on Netflix.