In the span of 16 years in the back half of the 19th century, Americans watched as two of their presidents were struck down by an assassin’s bullet.

Abraham Lincoln’s 1865 slaying at the hands of John Wilkes Booth is immortalized as a flashpoint in history at the end of the Civil War. But the shooting and slow infection-induced demise of our 20th president, James Garfield, in 1881 doesn’t carry the same notoriety. For most, it is a fact only rendered useful when trying to prove you paid attention in history class.

Garfield’s wife, Lucretia, says as much in the final moments of Death by Lightning, Netflix’s new four-episode account of the third presidential assassination in American history. Lucretia (Betty Gilpin) speaks to her husband’s assassin, Charles J. Guiteau (Matthew Macfadyen), through the metal bars of his jail cell, where he’s been sentenced to death for his failed plan to kill Garfield and earn a place in the administration of his successor Chester Arthur (Nick Offerman). The fleeting First Lady laments to Guiteau that he didn’t give her husband enough time in office — he was shot less than four months into his presidency — to make an impact and be remembered by history in any meaningful way.

“In reality, I know history won’t remember him at all,” she says through gritted teeth. “Be no reason to. A minor footnote at best. An idle piece of trivia.”

More on Netflix:

That last bit seems to be a knowing nod to Garfield’s status as a popular bar trivia factoid 140 years after his death. But she is right. Apple TV brought Lincoln’s assassination and the pursuit of Booth to the screen with last year’s limited series Manhunt. But Death By Lightning has a steeper hill to scale: to not only entertain but educate the masses about the three-month president and the mentally unwell man who took him from history.

“My hope is that people who watched the show are able to just sort of receive it as the tip of the iceberg,” series creator and writer Mike Makowsky tells TV Guide. “It’s a real privilege to be able to reintroduce James Garfield and the people of his era to modern audiences. I think that there’s a lot about Garfield’s journey that will hopefully prove very instructive to how we view politics in our country today, and I hope that the show puts forth a compelling enough argument that we should still care about him.”

Yet, there is even more to the story than the relatively short series has time to depict, much of it covered in Candice Millard’s book, Destiny of the Republic, on which the show is based. So we went to the source with Makowsky to talk about what did and didn’t make the cut in Death by Lightning.

Garfield’s Life

In Millard’s book, readers are treated to an extensive look at Garfield’s life, literally from the cradle to the grave. But Makowsky’s series stays almost exclusively between the goalposts of his shocking ascension to the presidential nomination at the Republican convention in 1880 and Guiteau’s execution for his assassination in 1882. Yet, Makowsky reveals he originally wrote six episodes for the series early on, in which he delved more deeply into Garfield’s younger years and role as brigadier general in the Civil War.

“In so many ways, he’s like a poster boy for the American dream,” Makowsky says. “He grew up in abject poverty, he’s the last president ever born in a log cabin. I had originally written this cold open for an episode that started as a flashback of him working on a canal and nearly drowning, which is a crazy story of him as a teenager. But it was going to be way too expensive to shoot. There’s always production concerns and budgets. We could have shown a ton of the Civil War battles in which he partook, too, but I think we had to choose our own battles at a certain point.”

Guiteau’s Trial

Perhaps the biggest omission from the series is Guiteau’s trial. In the fourth episode, interspersed with Garfield’s convalescence and subsequent death, there are a few fleeting glimpses of Guiteau behind bars, including one where he gleefully revels in his perceived celebrity to the astonishment of his sister, Franny (Paula Malcomson). But what audiences don’t see is the absolute circus that was his trial and conviction. Makowsky says his original six-episode run ended with a trial episode, inspired by his time reading hundreds of hours of court transcripts. He remains proud of what he wrote, but admits it didn’t quite fit in the two-hander story that ultimately made it to the screen.

“Once Garfield is no longer with us, it felt a little bit too much like the Guiteau power hour,” he says. “How much more do you really want to hear from the assassin after does the most heinous thing on the planet? Do you really want to see him muling up on the stand for another hour? I’m not really sure what it might have served aside from just being a fascinating piece of the story.”

Fascinating is an understatement though. At its core, Guiteau’s trial was one of the first in American history to see a case built on the mental illness defense. But Guiteau used every second of the two-month trial to his public-facing advantage. He was rarely deterred by his confinement and grim circumstances. He wrote a manifesto, or what he called a book, about why he shot Garfield and why it would help the country. He solicited a wife with a detailed newspaper ad: “I want an elegant Christian lady of wealth, under thirty, belonging to a first-class family. Any such lady can address me in the utmost confidence.”

When it came time to actually go to trial, he had his patent lawyer brother-in-law (yes, the one he steals from in the first episode!) represent him, even though he wasn’t a criminal lawyer. During the trial, he openly criticized his lawyer’s methods, referring to him as a “jackass” and shouting his frustrations with him to the audience and the judge. He repeatedly addressed the judge, which was not well received, and used swear words with impunity. When he wasn’t allowed to give his own opening statement, he handed a copy of it to the press in the room so they could publish it.

Everything you need for fall TV:

He spent a week on the stand going on about his life from birth onward. He overtly demanded that those who had raised money for Lucretia and Garfield’s family should also be raising money for his legal defense. Yet, through it all, 36 experts testified to his sanity, kneecapping his own lawyer’s defensive strategy to save him from the noose. While in jail, at least two attempts were made on Guiteau’s life, including from an officer who didn’t believe he was worthy of protection from the bloodthirsty mob outside. Another attempt came as he was being driven to court in a carriage.

Still, with all that delicious madness to mine, Makowsky is adamant indulging too much of Guiteau’s antics would have become celebratory rather than insightful. And frankly, some of it was just too bizarre, even for TV.

“There’s a handful of details that aren’t in the show that are almost so crazy that I think I would have been accused of making them up if I had put them in,” Makowsky says. “For example, Dr. Doctor Bliss. The first name of the physician tending to Garfield was Doctor. So his real name was Dr. Doctor Bliss. I mean, like, fire the whole writer’s room at that point! What are you going to do? Write a scene where you’re in this period of convalescence with Garfield and he’s clearly not doing well, but you have an aside where two characters go, ‘I’m sorry, his first name is Doctor?’ I think it would have robbed some of the impact of the situation at hand.”

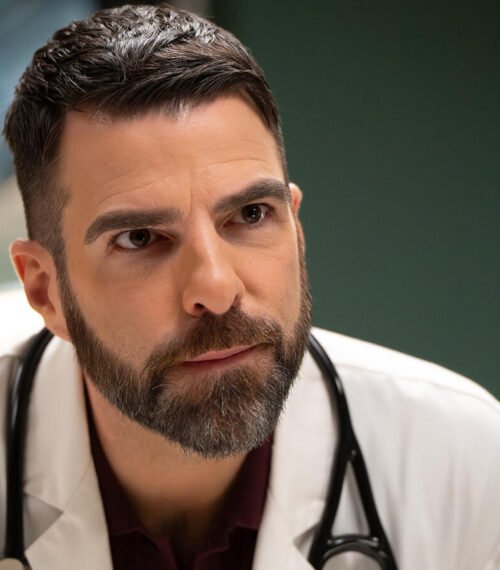

Garfield’s Slow Demise

The bulk of the fourth and final episode is focused on the medical malpractice that was Garfield’s treatment at the hands of Bliss (Željko Ivanek). Bliss is brought to Garfield’s bedside by his secretary of war, Robert Todd Lincoln (Kyle Soller), who knew him as one of the doctors who tended to his father on his own deathbed. However, the doctor was adamant that the bullet was in Garfield’s right side, and shunned any other physician who tried to assist in caring for the president (despite never actually being given the authority to do so). In actuality, the bullet was in his left side and an autopsy revealed had it been left alone, it would have never killed Garfield. Yet, Bliss prodded his wound for weeks after the shooting, creating infection and abscesses that ultimately cost the president his life. He was warned of this by the first doctor on the scene: Dr. Charles Purvis (Shaun Parkes), a surgeon at the Freedman’s Hospital, whose momentary care of Garfield made him the first Black doctor to attend to a sitting president. All of these moments are in the series, ripped right from the history books.

But one of the biggest revelations will likely be that Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone, played a part in trying to save Garfield. He used his induction balance, aka an early metal detector, to try and locate the bullet in Garfield’s back. Bell (played by Outlander‘s Richard Rankin), who was mourning the loss of his son at the time, was incredibly moved by the president’s plight and felt his invention could help. He met with Garfield, under Bliss’ watchful eye, but Bliss’ insistence that the bullet was somewhere it wasn’t made Bell feel inadequate. He struggled with not being able to help, something that wasn’t alleviated by the autopsy’s revelation he was looking in the wrong place. For years after Garfield’s death, Bell remained close with Lucretia.

Lucretia’s Midnight Meeting

One invention of the series, which comes after Garfield’s death, is the aforementioned scene when Lucretia goes to see Guiteau hours before his execution. This didn’t happen in real life (that we know of), but Franny did try to see Lucretia to advocate for her brother’s insanity defense (but was denied facetime with the grieving first lady). However, having Lucretia go face to face with Guiteau in the series gave Makowsky a chance to let Garfield’s biggest champion speak on his behalf.

“I wanted to have [Lucretia] give a voice to the ultimate thematic thrust of the series,” Makowsky says. “Every man in this show is obsessed with securing his legacy in the annals of American history. But the irony is that none of them are remembered today in any significant capacity. Not Garfield; not Roscoe Conkling, who was the most powerful politician of his era; or James Blaine, who may have been the second. Not Chester Arthur, certainly not Charles Guiteau. But [Lucretia] was the first lady at a time when women weren’t allowed to vote. They knew better than to think that they would have an enduring legacy. This is a male-driven obsession. So for her to be able to look her husband’s killer in the eyes and tell him that she has helped ensure that he will not have a legacy, like he ensured for her own husband, felt like such fertile, dramatic grounds and Betty is so outstanding in that scene.”

Having now spent so much time with this story, Makowsky says he is haunted by the what-ifs of [Lucretia] as first lady. What might she have done with the office? How might she have changed history in the ways she always expected her husband to?

“To be able to give her a fraction of that active ownership over her own story was such a rare privilege and, in many ways, it’s my favorite scene of the show,” he says.

Guiteau’s Execution

Despite his rather rowdy trial, Guiteau’s eventual execution on June 30, 1882 was a somber affair. The series faithfully recreates what happens when he takes his final steps into oblivion. He tripped on his way up the steps to the noose, turning to a guard and offhandedly saying, “I stumped my toe going to the gallows.” He interrupted the priest giving last rites and instead prepared an almost skit-like rendition of a bible verse, sung in a childlike voice. What he found, however, wasn’t an adoring crowd but a docile sea of 250 stone faces, who attended not to witness history but instead to see justice done. There is no way to know how Guiteau really processed this, but Makowsky speculated the moment could be summed up in one word: “Oh.” As Macfadyen swallows the sting of Guiteau’s final moment, he uses his last breath to utter the singular and certainly painful reality check.

“What I wanted to see from Matthew, and I think he executed it so beautifully, is the weight of reality finally crashing down on Guiteau,” he says. “Him realizing that what [Lucretia] told him the night before is true. He is not the hero of this story. He is not going to matter. These people are not going to be celebrating him and crying his name out in the street.”

Outside the prison, there were throngs of people waiting to hear that Guiteau was dead. But those who were there — a fraction of the 20,000 people who had requested tickets to watch it live — only cheered his demise. But the series doesn’t show that. Instead, it sits with the near-silent moment where Guiteau has to swallow the confirmation that even presidential assassins are forgotten.

Death By Lightning is now streaming on Netflix.